Rufus Sewell: ‘You felt he had loaned his magnificent intellect to you’

I worked with Tom when I was quite young, on Arcadia in 1993, and again on Rock’n’Roll 13 years later. In the interim it slowly dawned on me that not all jobs were like that. He was one of the most intelligent people you could ever meet but the extraordinary thing was that you’d walk away from conversations with him feeling like you were not unintelligent or unwitty yourself. That’s not always the case with incredibly brilliant writers and funny people. That generosity of spirit marked my time with him. He was incredibly good company, very sweet, and you felt encouraged to put forward your own ideas, make your own jokes.

That feeling, that he had loaned his magnificent intellect to you, was the same in his work. You’d see a play imparting all these competing ideas and you would leave abuzz and pretty confident you could explain it to your friends but you had to make sure that you’d worked out exactly how to do so before you reached Hammersmith because that was when it would start to evaporate. You would feel the benefit of his genius probably about as far as Barons Court.

I was doing another play when I had the rather frightening audition for Arcadia coming up. The night before my audition there was a knock at my dressing room. I didn’t have my clothes on and said who is it? A very particular voice answered: “It’s Tom Stoppard.” I grabbed a towel to put over myself and opened the door. He said it was the second time he’d seen the play, that it was a good production and that he knew I was coming in tomorrow and he wanted me to know “I’m on your side”. The process was still long and arduous – it wasn’t like I was immediately given the part – but it gave me confidence that, in the corner, there was this figure and I had his approval.

When we were doing Arcadia he’d be there festooned with scarves and cigarette smoke and in my peripheral vision I’d try to detect any shift signifying approval or disapproval – a leg being crossed or uncrossed, a scarf being rearranged, a puff of smoke. In his writing there was a blokiness that really counteracted the kind of heavy intellectual quality. He knew the difference in language between a “dick” and a “prick”. I was aware in rehearsals of him changing a line because he felt it was too writerly, that it needed something to take the edge off. So, despite this brilliance he was famous for, if something felt even remotely page-bound he was bothered by it.

Christine Baranski: ‘How do I measure up to that level of dazzling wit?’

You shouldn’t wait until someone’s memorial to tell them how much they meant to you. So I’m happy to say that a few years ago I had Tom and some of the cast from The Real Thing, which we did in New York in 1984, over to my apartment. We toasted him and told him it remained the most special theatre experience of our careers.

We were all a bit concerned about Tom’s smoking but I knew he’d want to smoke. I had an ashtray I’d kept from the Brasserie Lipp in Paris years earlier when I was there with my 16-year-old daughter and, at the table right next to us had been Tom and Mick Jagger. I gave it to Tom, opened the bay window for him, and he had a couple of American Spirits. The ashtray with its two butts is still on my bookshelf.

The Real Thing was an enormous Broadway hit – we won Tonys – but I’d go home at night thinking: I’m not smart enough to be in this play. I’m going to have to fake it. For one thing I was an American actor being terribly English but the challenge, like with Stephen Sondheim, was how do I measure up to that level of dazzling wit? The whole experience was elevated. We were swimming in the mind pool of Tom Stoppard – a very privileged place to be. As you do with Shakespeare, you feel like you’re on a higher plane.

Anyone will talk rapturously of him. I remember him coming to rehearsals in these soft, buttery suede jackets, with that tousled hair and those voluptuous lips. We all had a crush on Tom. He was very stylish, the closest we’ll ever come to knowing a Wildean character. Later, when I was filming Mamma Mia! for many weeks in England, we were trying to meet but were both very busy. On my last day in London he took me to tea and said: “I’m rather ashamed of myself. You’ve been a guest in my country all this time and I’ve not taken care of you.” Such a gentlemanly thing to say.

He could be extraordinarily astute. What struck me most was that he could have directed his rapier wit to cruel effect, but I never saw any kind of mean-spiritedness in him. He enjoyed being Tom Stoppard – and was sort of an invention. It was as Tomáš Sträussler that he had come to England and he loved his English upbringing.

One of the first plays I ever did was The Real Inspector Hound in Baltimore. That was such fun. I particularly loved doing Stoppard because of his great ability with language. You could just send a sentence over with a certain degree of top spin and it would delight an audience.

Susan Wokoma: ‘He was always a WhatsApp message away’

You cannot be cast in a major Tom Stoppard production without Tom Stoppard’s approval so the fact I got to be in The Real Thing in Tom’s lifetime is something I will cherish for ever. We were told he was seriously ill as we started rehearsals – nevertheless he was always a WhatsApp message away with answers to our many questions that arose from such a tremendous and terrifyingly adored text. We could hear and feel Tom’s yearning – this was the first time such a production was being mounted without him in the rehearsal room. As a company we wanted nothing more than to make Tom proud.

Then, the Saturday before press night, our company stage manager, Rebecca, tells us that, despite being warned against travelling, Tom has come to see the show. I’ve known the fearless James McArdle – our resplendent Henry – since we were 18 and 19 years old and I’ve never seen him so terrified.

We were instructed to return to the auditorium to meet Tom once the audience had left. There we had an intimate “audience with …” that I will remember for the rest of my life. And most importantly he loved the production, the first major revival for which he had been completely outside the rehearsal process. Generous, thoughtful, funny and kind – he was everything I imagined him to be.

“This is the last time I’ll see this play,” he said. The enormity of the words hung in the air. “But I’ll outlive all of you.” How right he was.

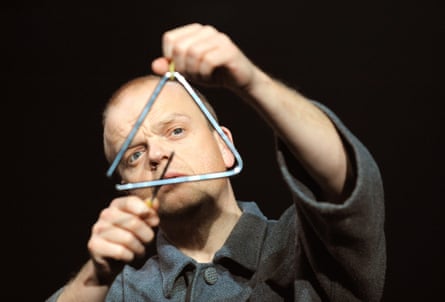

Toby Jones: ‘The plays are full of cracking gags’

Everyone talks about Tom’s genius but in Every Good Boy Deserves Favour you also had this other side to him as it is such a brilliant conceptual piece of stagecraft. The idea of having an orchestra live on stage and making the audience complicit with the actuality of the orchestra and thereby with a person who is supposed to be hallucinating. You might not associate that visual stagecraft with him although there are the acrobats in Jumpers and the River Styx in The Invention of Love. His openness to the experiment of the National production, which brought dancers among the orchestra in a deviation from the original play, was really striking.

My father shared a house with Tom when he was writing scripts for Mrs Dale’s Diary and he had strong memories of the cigarette smoke as Tom pounded out episodes. He was a big figure in my life from those stories and then at school I remember studying Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead for A-level. Like Pinter, he was one of the giants of theatre that our generation grew up with. So when I finally met him it was a thrill to find him so personable.

When Tom and I went on a coach trip together to the Calais Jungle it gave me a prolonged time to hear him talking about the precariousness of these refugees and his personal connection with that situation. We crisscrossed a bit after Every Good Boy and he always had this wonderful warmth – the opposite of someone being too brainy to chat with you. The plays are full of cracking gags and there’s an appreciation of the different registers of drama, that on the one hand it’s a collision of ideas but also the theatre is a place of the gut and of guffawing.

Harriet Walter: ‘No one gives the skivvy a book token but Tom did’

Everyone on this page has been unbelievably lucky. We all knew Tom Stoppard. We lived at the same time as him and basked in his brilliance up close. When I was 18 and not yet even a drama student I was a skivvy in charge of the props for the world premiere of Tom’s After Magritte. He was a very romantic, fleeting visitor to the rehearsal room. I treasured a £5 book token he gave me for the opening performance. No one gives the skivvy a book token! Tom did.

Cut to much later and I am playing Lady Croom, the flighty over-sexed mother of Thomasina in the first production of Arcadia. We all learned a bit about chaos theory among many other subjects that Tom had brilliantly tied together in the play. Luckily, Lady Croom didn’t have to understand chaos theory, only to cause chaos with her rampant sexual appetite, that rogue ingredient that can’t be controlled, explained or predicted. I had lines that were so funny I often couldn’t get to the end of them before the audience drowned me out with laughter. What ecstasy. What a gift from Tom.

Every other line in Arcadia dazzles, but Tom didn’t intend to show off. He was genuinely delighted by asking questions and sharing everything he discovered. And he managed to infiltrate some of the most profound messages about life, art and the physical universe into the comic weave. In Arcadia he puts an end to the art v science division. He brings them together, illustrating the imaginative beauty of science and the calculated order within art.

Thomasina Coverly, the 13-year-old genius in the 19th-century part of the play, can grasp mathematical concepts that fly over most of our heads. She can spot the physical principle at work in the stirring of jam into her rice pudding. Hers is the first line in the play and it is a question. She is endlessly curious and deep-thinking while still being childish and playful.

She is cerebral but also passionate – she is moved to tears by the destruction of the great library of Alexandria, and when the play moves forward three years she matures into a romantic young woman in love with her tutor, and although she dies in a fire on her 16th birthday, her calculations live on for future generations to interpret with wonder. I believe all this to be true of her near namesake Tomáš Stoppard.