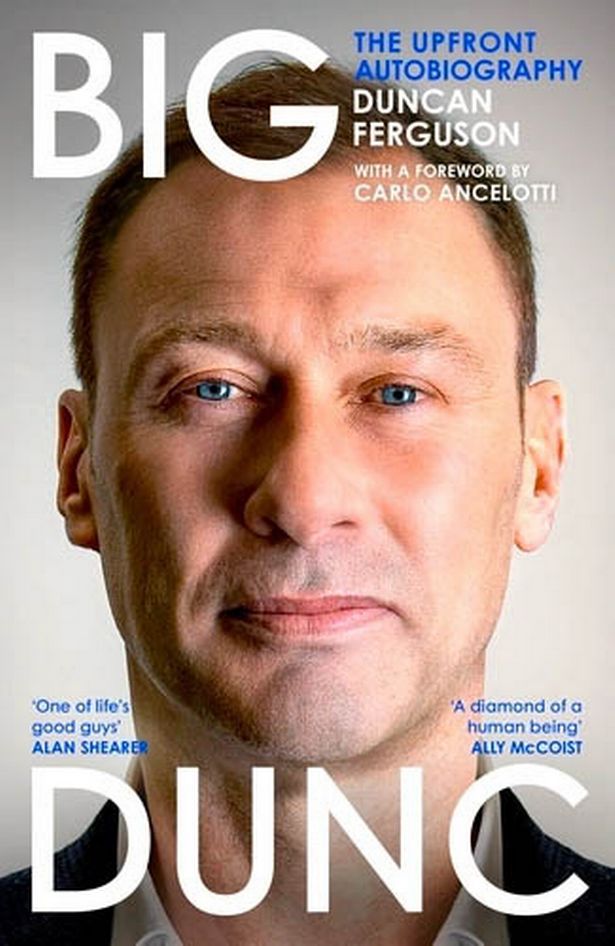

Everton hero Duncan Ferguson was sentenced to three months at the infamous Barlinnie prison in Glasgow – now he speaks for the first time on his terrifying time inside

19:30, 02 May 2025Updated 19:40, 02 May 2025

I believe I’m a brave man, tough physically and mentally, but when I was led handcuffed into HMP Barlinnie on October 11, 1995, my blood ran cold. I was only 23 but my life was on hold, even at risk. I was entering Britain’s most notorious prison with its huge stone walls, barbed wire wound around the top and forbidding metal doors that had all the charm of the brass plate on a coffin.

Outside, I was Big Dunc. Striker. Everton and Scotland targetman. Inside, I was the target. And I was terrified. I’d just lost my appeal against a three-month sentence for what the courts claimed was an assault on another player, Raith Rovers’ John McStay, at Ibrox Park on 16 April 1994. I hardly grazed the boy, I promise you.

It happened while I’d been playing for Rangers in Glasgow and I just ended up feeling like some people in the Scottish judiciary didn’t like the club. They were probably delighted to see me banged up in Barlinnie.

As I entered the prison, I thought, “What on earth is happening to me? What’s happening to my life? How has it come to this?” Yes, I connected with the lad, but to face this hell because of that incident felt terribly unfair.

I was marched through the small, dingy reception area and into the holding cubicles, known as doggy boxes. I sat for several hours on a bench inside, with food and cigarette butts on the floor, and graffiti on the walls, surrounded by men with “Mars bars” – scars.

READ MORE: Duncan Ferguson: I told David Beckham to f*** off – it’s one of my biggest Premier League regretsREAD MORE: DUNCAN FERGUSON Football’s greatest hard-man sets the record straight on fighting, partying, prison and more

Everywhere I looked I sensed menace. My stomach knotted as I completed the cold, clinical elements of being processed. Clothes off. An invasive inspection. A lingering sense of humiliation.

Unsmiling guards gave me my number – 12718 – and handed me my gear, a red shirt with white stripes and blue denim trousers. Every part of the process dehumanised me further.

Everyone in Barlinnie knew I was coming. It was all over the news I’d lost my appeal. I was the first British footballer imprisoned for something that had happened on the pitch. Three months. The “brevity” of my sentence meant I couldn’t be transferred to an open prison or an English jail.

It deepened my anger at the verdict. But my new neighbours weren’t bothered about the rights and wrongs of the decision. They just wanted to see this famous footballer. The one who’d broken the British transfer record with a £4million move to Rangers from Dundee United.

The one who had played for Scotland. And the one who had helped Everton win the FA Cup within a year of coming to the club. What a fall from grace. Earlier in the day I’d handed my watch, rings and some cash to my dad as I left the courtroom in Edinburgh. God only knows what my mum and dad were feeling, with everything I was putting them through.

All I had in my pocket was £5 to buy some phonecards – prison currency – as I was taken by guards from the doggy box towards my cell in D Hall. It was late afternoon, early evening. Processing had taken three hours. I was classed as a Category D prisoner, which meant I was considered unlikely to make an effort to escape. The only effort I made was not to betray the fear growing inside me as

I stepped on to the metal spiral staircase connecting the ground floor to the four floors above it. I was still a kid in many ways. Hearing the keys clanking and the locks rattling shut was terrifying. I’d just lost my freedom.

But I was determined not to lose my mind. I’m strong, I told myself. And I needed to be. The name Barlinnie carried a grim association, with condemned men imprisoned for crimes ranging from gangland violence to multiple murders, the Lockerbie bombing to paedophile depravity. The name alone was enough to send a chill down the spine. Mine, anyway.

Barlinnie is home, they say, to Europe’s busiest methadone clinic, with statistics suggesting up to 400 inmates are injected daily with the heroin substitute. The atmosphere was claustrophobic and oppressive, exacerbated by chronic overcrowding. Slopping out, an unspeakably degrading practice, not to mention a fundamental breach of human rights, was abolished only in 2004.

Barlinnie’s uncompromising reputation meant I was well aware I’d have to stand up for myself from the outset. Predators prey on the weak and there are plenty of both in there – with no means of escape until your time is up.I looked around my cell on that first day and quickly took in the window with metal bars, a bed, a rickety little table and a pot in the corner.

(I honestly didn’t know what the pot was for at first. I would find out the next morning. No en-suite here.) On that first evening, lights out came at 10pm prompt, but then the night sounds began. It wasn’t long before a thick, sinister Glaswegian voice cut the atmosphere like a knife.

I’m Protestant, at a Protestant club, Rangers. Being in a prison in Glasgow, with half the joint supporting Catholic club Celtic, meant sectarianism flowed through Barlinnie like sewage from a broken pipe.

“Ya dirty Orange b*****d, Ferguson, I’m gonna f***in’ kill ya!” Several more brave boys took up the cudgels. “Ya’ll get it in the mornin’, ya big Orange ****!” “We’re gonna slash your f***in’ face!” I sat at the end of my bed listening to all these threats, shaking.

On it went. It was hard to deal with, it wasn’t how I was brought up. Sectarian songs weren’t the soundtrack of my life in my home town of Stirling, not like in Glasgow. In fairness, if I’d been a Celtic player the Rangers fans would have been just as tough on me. The dire warnings continued unchecked until a single heavy Glaswegian voice boomed out with all the authority of a man accustomed to being listened to.

“Shut up, the lot of ya. I want to get my head down and sleep. The next f***er who opens his mouth, he’ll answer to me in the mornin’.” The whole nick went quiet. Bang, dead. I never found out who he was, and I would learn that those boys tend to protect their anonymity.

But I would also discover that during my time in Barlinnie there were certain people looking after me. I never heard another word directed at me that night, not a peep.

But, believe me, it was the longest night of my life as the images of a blade kept me awake. Welcome to hell.

Big Dunc: The Upfront Autobiography by Duncan Ferguson, with Henry Winter, is published on 8th May by Century

Join our new WhatsApp community and receive your daily dose of Mirror Football content. We also treat our community members to special offers, promotions, and adverts from us and our partners. If you don’t like our community, you can check out any time you like. If you’re curious, you can read our Privacy Notice.

Sky Sports’ discounted Premier League and EFL package

Sky has slashed the price of its Essential TV and Sky Sports bundle in an unbeatable new deal that saves £192 and includes more than 1,000 live matches each season across the Premier League, EFL and more.