By ZOE HARDY

Published: | Updated:

Michael Hughes says he spent years feeling inferior to other men with ‘perfect hairlines’.

While his friends experimented with short back and sides or bleached buzz cuts, the 37-year-old – whose hair began to recede in his late teens – would look in the mirror and feel helpless. For years he put up with it, telling himself it wasn’t that bad.

But after seeing photos of himself, then 35, on holiday with his wife and two children, something snapped.

‘That was really the turning point for me,’ says Michael. ‘I was looking at the photos taken on a boat trip, and I just couldn’t stop thinking how stupid I looked. The wind had blown my hair back and I looked awful. I was left feeling more deflated than ever and knew I had to do something.’

Like thousands of British men every year, he began looking into hair transplant surgery. Michael continues: ‘My brother, who is also balding, told me to shave my head and embrace it, but I just couldn’t.

‘I thought a hair transplant would be an easy fix and make me feel better.

‘You’d see people going through the process and showing off the results on social media – even footballers talked about having it done. I knew people who had travelled to Turkey to get a transplant and it looked perfect – they were in and out in a matter of hours and you would never know they’d had a transplant, the hair looked so natural. That’s what I wanted.’

But things didn’t go to plan. Instead, the operation marked the start of what Michael says has become an ongoing ordeal that has badly damaged his mental health.

The results, he says, were disastrous – leaving him with a patchy hairline and grafted hairs growing at unnatural angles, nearly an inch above his original hairline.

He has agreed to share his story in the hope that other men thinking about surgery will carefully consider the possibility of things going wrong before going ahead.

Michael says he felt confident when, in August 2023, he booked his transplant at a cosmetic clinic offering anti-ageing procedures. He’d seen five-star reviews online and the clinic was offering a half-price deal – £2,495.

He was further reassured after a consultation with his surgeon.

Michael said: ‘He said all the right things – about how he would avoid the “pluggy” look by placing single hairs in the hairline, and angle them in a natural way. He showed me some results from Turkish clinics to warn me what a bad transplant could look like.

‘He explained about the shedding phase, the hair life cycle and told me how important it would be to take anti-hair loss medications finasteride and minoxidil from then on.

‘He said everything I expected to hear and seemed very genuine.’

Modern hair transplants use a technique called follicular unit extraction (FUE), where individual hair follicles – each typically containing one to four hairs – are harvested from the back of the scalp and implanted into thinning areas.

This minimally invasive method leaves no visible scarring and typically offers a far more natural-looking result than older versions of the procedure.

On the day of the operation, Michael says he was told about 500 follicular units would be enough to restore his hairline around the temples. The procedure itself, however, was extremely uncomfortable.

‘It took a lot longer than I expected,’ he says.

‘After lying face down for approximately three hours for the extractions, I felt faint – I had to have an hour-long break.

‘The implantation stage took a further seven hours, and the anaesthetic kept wearing off so by the end it was quite painful.’

While the extractions and incisions were carried out by the surgeon, the implantation was performed by an unnamed doctor and a technician. After ten hours in the clinic, Michael’s wife picked him up and drove him home.

The next morning, expecting to see at least a more defined hairline, Michael was devastated.

‘There was heavy scabbing over the grafts and a big gap between them and my existing hairline that had literally nothing in it.’

He emailed the clinic with his concerns but says he was reassured the appearance was normal. ‘I took them at their word,’ Michael says.

Ten days after the procedure, he still couldn’t see any improvement – in fact, he thought it looked worse.

‘There were a lot of gaps with no hair when the scabs came off. I made a post online looking for reassurance but got quite the opposite. It was brutal,’ he recalls.

‘Every single comment was negative – some people even said it was the worst result they had seen in a long time. One asked if I’d had it done in an alleyway.’

Michael again contacted the clinic and was told the gaps would be covered as the hair grew. He was also reassured that if any adjustments were needed, he would be seen free of charge.

‘This improved my mood and I decided to wait it out, with the hopes that it would turn out OK. Either way, there was nothing I could do about it by that point.’

But over a year later, Michael was still struggling. ‘Those 18 months were the worst of my life,’ he says. ‘It consumed my life.

‘I was angry, depressed and annoyed, and my wife got the brunt of it.

‘Everyone told me I should never have had the transplant in the first place. Even my kids said I looked stupid. I felt like it was my fault and I was embarrassed.’

On the advice of other men online, and having lost faith in the clinic, Michael approached hair transplant surgeon Dr Ted Miln in May.

Dr Miln told him he would need at least two more procedures – one to remove as many of the original grafts as possible, and another to reconstruct a new hairline and fill the thinning areas.

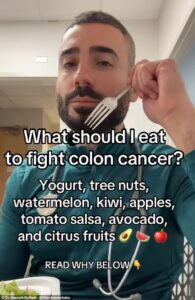

In a video posted to Instagram highlighting the toll a bad transplant can take, Dr Miln said: ‘It is very very far from an aesthetic result.

‘Michael has been left with very unnatural-looking channels in between his natural hairline and the transplanted one.

‘The transplant hasn’t done anything for Michael’s confidence and he has had to hide it.’

Ryan Moon, a patient consultant at Dr Miln’s clinic, says they’re seeing a growing number of men unhappy with the results of previous hair transplants.

Hair transplant failure rates are not always openly published, partly because many clinics lack long-term follow-up data or are reluctant to disclose poor outcomes. However, clinical studies and expert estimates suggest the failure rate ranges from five to 15 per cent – depending on factors such as the technique used, clinic standards, surgeon expertise, aftercare and the patient’s overall health.

According to Mr Moon, medical tourism has exploded – particularly to countries such as Turkey where clinics promote ‘unrealistic results at bargain prices’. Just yesterday it was reported that a 38-year-old Briton had died while having a hair transplant in the country.

But poor surgery is also happening in the UK, too.

‘We’re seeing an epidemic of botched hair transplants,’ says Mr Moon. ‘You have surgeons dipping their toes into hair transplants who don’t do the procedure full-time and simply aren’t experienced enough.

‘Some clinics operate like conveyor belts, and patients get virtually no time with the surgeon.

‘They aggressively advertise to young men via social media.

‘The effects of a bad hair transplant on someone’s emotional and mental wellbeing are often far worse than the initial hair loss – it’s devastating.’

He adds: ‘A hair transplant is not a simple procedure. There’s a lot to consider, such as the angle of the graft and creating a natural-looking irregularity along the hairline.’

The British Association of Hair Restoration Surgery (BAHRS) says more than 100 doctors in the UK now offer hair transplants, with the industry expected to be worth £335 million by 2030 – a sizeable chunk of the £6.5 billion global market.

But with rising demand, new problems have emerged. Spencer Stevenson, who underwent more than five hair transplants and spent over £30,000 on corrective procedures, now works as a patient adviser.

He warns: ‘The harsh reality is that many of these procedures are being carried out, not by qualified surgeons, but by untrained, unlicensed technicians. There are glossy adverts, but we hear about clinics making misleading claims and false promises.’

Because transplant surgery involves cutting the skin, any clinic in England has to be registered with hospital watchdog the Care Quality Commission (CQC).

But beyond this, there’s only guidance – not legislation – on good standards of practice.

The Cosmetic Practice Standards Authority recommends that all surgical steps in a hair transplant should be carried out by General Medical Council-licensed doctors – but, again, there is no legal requirement to follow this.

Meanwhile, the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery (ISHRS) has warned of ‘a growing number of spas and medical offices that do not specialise in hair restoration using unlicensed technicians to perform all or some aspects of hair restoration surgery’.

Mr Stevenson adds: ‘Hair transplantation is a highly specialised form of surgery – it should never be delegated to unqualified or inexperienced technicians. You wouldn’t trust a trainee learning on the job to perform your heart bypass, so the same level of scrutiny should apply here.

‘And just because a practitioner is a surgeon doesn’t mean they’re qualified to perform hair transplants – patients should be looking for a surgeon that performs the procedure full-time.’

Michael’s transplant journey is far from over – he’s due to go back under the knife in four months.

He says: ‘If I’d known how wrong things could go, I wouldn’t have gone through with it. I would have just shaved my head.’