By JOHN NAISH

Published: | Updated:

Jackie O’Carroll was ‘a busy mum of three’, working in HR at Rotherham Council, when she underwent surgery to treat urinary incontinence caused by childbirth.

‘When I was out jumping around with the kids, I was a bit incontinent,’ she recalls. ‘Surgeons at my local hospital said I might have a prolapse and they had a gold-standard surgical treatment.

‘The doctor drew a diagram – and from that it seemed that they were going to use one of my own tendons as a sling to hold up my bladder,’ she says.

But straight after the operation, Jackie says, ‘I felt like my pelvis was on fire. I knew something was not right. But the medical staff said everything would settle down.’

It didn’t. ‘In a sense the op had worked, as I no longer had urinary incontinence,’ she says. But I constantly had this agonising, scraping pain in my pelvis. Months turned into years and it didn’t go away.

‘My GP was throwing painkillers at me and I ended up on morphine. I was so worn down I couldn’t do much with the kids. And intimacy with my husband stopped; it hurt too much.’

At one point Jackie’s mental health plummeted and she took to her bedroom, not dressing, hardly eating.

‘It took me months to get back into the world of the living,’ she says. ‘Nevertheless doctors still told me the pains were in my head.’

Then, seven years after her surgery, Jackie learned that, in fact, rather than her own tendon, a form of surgical mesh had been used to support her bladder.

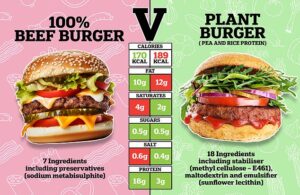

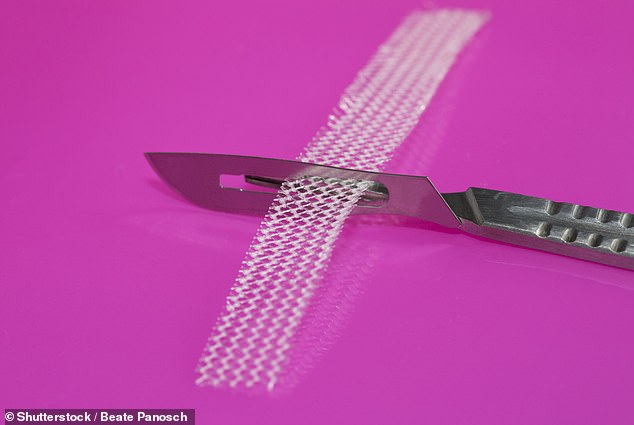

She was one of the thousands of British women harmed by polypropylene pelvic mesh implants that had eroded and hardened inside them, causing chronic pain and other symptoms that ended careers, harmed families, ruined sex lives and destroyed marriages.

Five years ago, it seemed that these women had finally won their fight for justice.

Following a campaign championed by the Daily Mail, an official review, First Do No Harm, recommended that all new pelvic mesh insertion operations be paused for safety’s sake, that hospital records should be trawled through to find all women harmed by mesh, and injured victims be compensated.

But on the fifth anniversary of the review’s publication, campaigners say that most of the review’s recommendations have not been implemented – leaving mesh victims without justice or redress – and, as Good Health can reveal, with more women having their health threatened by new NHS mesh operations.

Kath Sansom, founder of the Sling The Mesh campaign, told Good Health: ‘The Government has dragged its feet on the most critical reforms.

‘Women are without state compensation and still being failed by a health system that was supposed to protect them.’

Evidence shows that despite the review’s call for a pause on women’s mesh operations, surgical mesh is being implanted into women on the NHS as an add-on to silicone breast implants after breast cancer.

As Sharon Hodgson, Labour MP for Washington and Gateshead South, who chairs the All-Party Parliamentary Group for First Do No Harm, told Good Health: ‘To have this little progress five years on from the publication of the report is hugely disappointing.

‘Crucially, thousands of women and families who were irreversibly harmed through no fault of their own are yet to see compensation because ministers have not acted on the First Do No Harm review recommendation,’ she says.

‘Money will not make up for all they have endured – but it would at the least remove the financial burden placed on their lives.’

But there is concern payouts could take years or even decades.

Last month, Sir Brian Langstaff, chair of the public inquiry into the infected blood scandal – where more than 30,000 people in the UK were given treatments infected with HIV, hepatitis C and/or hepatitis B between the 1970s and 1990s, causing more than 3,000 deaths – warned that thousands of victims are being ‘harmed further’ by long waits for compensation.

That same week Sir Wyn Williams, head of the inquiry into the Post Office scandal, criticised the ‘formidable difficulties’ facing the 10,000 victims claiming redress from a system he called slow and ‘unnecessarily adversarial’.

Jackie, now 54, does not expect to see compensation in her lifetime for the devastation mesh caused her – including, as with many mesh victims, years of being dismissed by doctors for ‘imagining’ her pain.

In 2017, a friend sent Jackie an article about Ms Sansom and her Sling The Mesh Campaign.

She recalls: ‘The penny dropped. I wasn’t this crazy woman. I went straight to my GP with the information and she agreed I had the same symptoms that Kath described.’

Jackie was referred to Pinderfields Hospital in Wakefield. Surgeons confirmed she did have the mesh implant and that it could be removed.

‘I didn’t have the op until 2019,’ says Jackie. ‘By then I had lost my beloved job at Rotherham Council because I could no longer function. After the op, I was told the mesh had been removed. But still I had problems with pain, even though my incontinence had not returned.’

Jackie demanded to see her notes, which showed that only a part of the mesh had been extracted. She was promised a further operation.

‘But then Covid happened,’ she says. ‘Finally, I had the operation at Manchester Royal Infirmary last year, but while they removed much more of the mesh, they said they were not equipped to take all of it out.’ Now Jackie has been referred for intricate urology surgery by specialists at Bristol Royal Infirmary and is awaiting a date.

‘They say the remaining mesh can be removed, but I will end up with a stoma [so will have to have a colostomy bag],’ says Jackie.

‘This may be temporary or permanent. But if I am finally free of pain afterwards I won’t mind.

‘I feel the most positive I’ve been for years, because there is a light at the end of the tunnel – no longer having this thing inside, poisoning me. But I have no hopes for financial redress for all my losses.’

Jackie adds: ‘Like with infected blood, it’s getting dragged out for so long that if there is any redress I expect it will go to my children, not me, because I won’t be around to see it.’

And now Good Health has learned a similar style of polypropylene mesh is being trialled in the UK for breast reconstruction operations after cancer treatment and in cosmetic surgery.

This is being led by John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford and conducted at five NHS hospitals in London and South East England.

Ms Sansom told Good Health: ‘We are aware of a current UK trial called Restore B, comparing silicone implant only with silicone implant plus mesh in breast cancer reconstruction operations. The patient leaflet does not warn of mesh risks.’

She says Sling The Mesh learned of the trial through one of its members who previously suffered a pelvic-mesh injury, and who later developed breast cancer and was offered mesh as part of her breast reconstruction. ‘She was horrified,’ says Ms Sansom.

A spokesman for the University of Oxford confirmed that some women in the trial would receive a mesh implant containing polypropylene, but added that any prospective patients would be warned beforehand ‘of all known or reported complications from other mesh-related surgeries, even though these are not known to apply to breast surgery’.

Ms Hodgson says she is ‘very concerned about wherever and whenever mesh is used’.

‘I believe it should only ever be used in a life or death situation.

A spokesman for the Department of Health and Social Care told Good Health: ‘The harm caused by pelvic mesh continues to be felt today.

‘Our sympathies are with those affected and we are fully focused on how best to support patients and prevent future harm.’