By GUY ADAMS and ROSS CLARK

Published: | Updated:

The Drax power station cooling towers loom ominously over North Yorkshire, dominating the skyline from Howden to the Humber.

Five per cent of Britain’s electricity comes from its gargantuan furnaces, which started belching out smoke in 1974.

Back then, they were fed by coal from nearby Selby, but in more recent times the facility has been converted to run entirely on processed wood pellets, a fuel known in the trade as ‘biomass’.

Under this arrangement, which dates back to 2012, the Government can officially describe Drax’s electricity as ‘renewable’. But critics, who call the whole thing a ‘great green hoax’, believe it’s anything but.

They have for years argued that the station, which has so far burned through the equivalent of 300million trees (via pellets shipped mostly from North America) is instead a major polluter, which produces more climate-destroying carbon than any other industrial facility in the UK.

The other thing Drax burns through is public money. Lots of it.

Last week, it emerged that the station’s privately-owned parent company was handed a stonking £869million in Government subsidies in the past 12 months alone.

That’s the equivalent of more than £2million a day, adding an estimated £10 to the energy bills of every household in the land. If the station really was ‘green’, one could perhaps consider this money to be well spent. But if critics are correct, you and I have instead helped funnel billions to the business – which last year made £850million in profits and enriched shareholders to the tune of £97million via dividends – for no good reason.

All of which brings us to a quite extraordinary legal case that unfolded at the London Central Employment Tribunal late last month. At its centre was Rowaa Ahmar, a former civil servant who was a top lobbyist for Drax over a period of roughly 18 months, between August 2022 and last January.

Ahmar was the power firm’s head of public affairs and policy for the UK. But she’d left the role in hostile circumstances and was now making a truly sensational claim: that she’d been unfairly dismissed for making whistleblowing complaints.

Specifically, Ahmar alleged that the firm sacked her after she wrote a series of bombshell memos telling senior executives that the company was ‘misleading the public, government and its regulator’, Ofgem, about the power station’s sustainability.

She told the court that Drax had attempted to ‘silence’ her as part of a plot to ‘deliberately conceal’ the truth, and accused the firm of telling porkies about the original source of the wood pellets it burned.

The case, which was heard over the course of a week in a ground floor room at Victory House in Holborn, London, revolved largely around fallout from the release of a documentary called The Green Energy Scandal Exposed, published by the BBC’s Panorama in early October 2022, shortly after Ahmar’s arrival.

It had made a deeply troubling claim: that Drax, which had by then received £6billion in green subsidies, was fuelling its supposedly climate-friendly biomass furnaces using wood that had been sourced from ancient primary forests in Canada.

This revelation gave lie to Drax’s insistence, aired in its PR materials, that it only ever used pellets made entirely from ‘sustainable wood’ such as waste sawdust.

Importantly, the power company chose to deny many of Panorama’s allegations. However, Ahmar insists that several of its PR lines were completely untrue.

Her jaw-dropping testimony, which includes an 80-page witness statement about which she was cross examined over three days, was chock full of unflattering insights into the culture at Drax.

It depicted it as a business with a cavalier attitude to public money, which was dysfunctionally run and seemed bewildered as to why anyone might want to question its practices. It should at this stage be stressed that the power firm disputes these and many of Ahmar’s other claims.

It points out that several of its own witnesses, who might have disputed her version of events, were denied the chance to take the stand because the case ended before its conclusion (in circumstances we shall detail later).

Back to the tribunal. At one point in her evidence, Ahmar said the Panorama episode triggered ‘a level of chaos that I have never seen before’ within the company, in which senior executives attempted ‘to find loopholes’ in an effort to dig themselves out of a crisis which had quickly wiped hundreds of millions of pounds off the firm’s market value.

She also alleged that a dishonest rebuttal campaign had begun the morning after the programme had been broadcast, with Drax posting a stern statement on its website which accused the BBC of repeating ‘inaccurate claims about biomass’ which ‘have for years been promoted by those who are ill-informed about the science behind sustainable forestry and climate change’.

Drax’s statement went on to assert: ‘Eighty perc ent of the material used to make our pellets is residues, sawdust, wood chips and bark left over when the timber is processed. The rest is waste material left over which would otherwise be burned to reduce the risk of wildfires and disease.’ Ahmar – who says she wasn’t consulted on the PR statement, despite being head of public affairs – told court that it took her a few hours to establish that much of the statement was completely untrue.

At another point that week, Drax received an email from the Department for Business, Enterprise, Innovation and Skills (BEIS) demanding a response to Panorama’s various claims. According to Ahmar a junior employee replied, without taking any advice, denying that Drax had received any material from two forests that had featured in the BBC film.

‘The programme targeted two sites – we have not received any material from these two sites,’ her message claimed.

That denial – made, it should be stressed, in an email to Government – also turned out to be false.

To this end, Stuart Cotten, Drax’s director of compliance and regulation, emailed colleagues to say the firm was in fact likely to have ‘consistently’ burnt pellets from Meadowbank and Burns Lake – the two precious sites in the BBC documentary – since ‘at least 2019’. Ahmar recalls that Cotton ‘said if we had used these pellets… we would have committed a significant misreporting of burn data’. Yet for some reason, she told the court, Drax let its denials stand.

It is important, at this stage, to understand the bizarre rules governing ‘green’ subsidies that British taxpayers currently finance.

They stipulate that Drax is actually allowed to source 30 per cent of its wood pellets from unsustainable sources.

That may sound scandalous – and from an environmental perspective, it probably is – but this loophole means Drax would not be breaking any rules if did burn some wood from virgin forests. By the warped logic of UK officialdom, that is supposedly less damaging to the environment than burning coal, since trees absorb carbon when they re-grow.

Crucially, however, what the company absolutely must do, under Ofgem rules, is to keep records of the exact source of all its pellets. It also has to be honest, and not make claims that it is only burning forestry residues when it is not. Drax’s problem, of course, was that it seemed to be doing the exact opposite. And as public controversy grew, some of the junior staff began to rebel.

One, says Ahmar, told her that he thought Drax ‘was greedy and would get caught’, and that he was embarrassed to work there, adding: ‘I will do the bare minimum and take my salary whilst looking elsewhere.’

As for how to deal with further government inquiries, Ahmar says she was advised by Drax’s head of media: ‘Why don’t you tell BEIS civil servants to f*** off?’ An odd way to display gratitude to the Whitehall machine that was showering them with cash.

With the PR crisis deepening, Drax hired KPMG to carry out an investigation into the scandal.

Ahmar said the firm produced a number of reports (though she claimed that not all of them were later shared with Ofgem). She claims to have been briefed on the interim findings of one, which confirmed that the company ‘in fact used unsustainable wood’, but was told not to discuss them with senior managers.

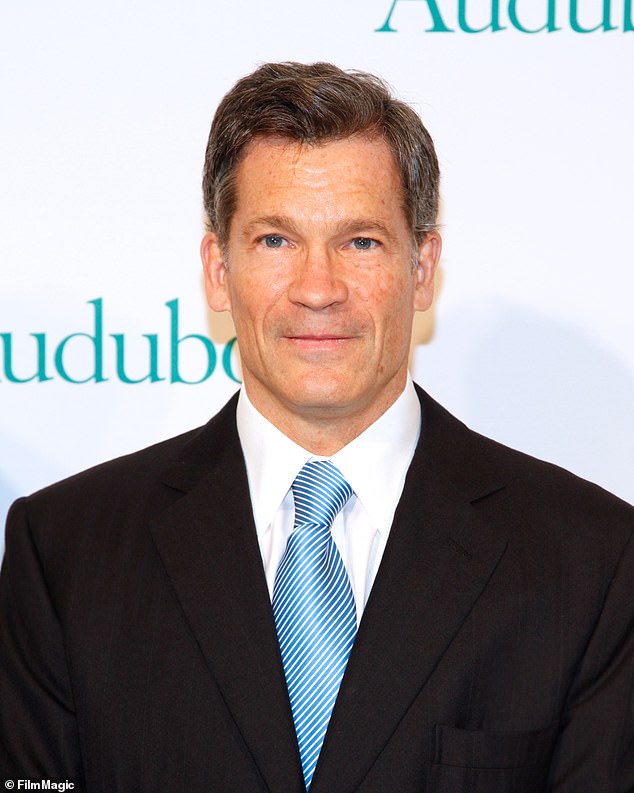

On November 2, she nonetheless decided to blow the whistle, sending a letter to Drax’s chief executive Will Gardiner – who earned more than £5 million in 2022 – saying the firm ‘had likely broken its legal obligations owed to its government funders by misrepresenting its biomass as being sustainable in order to obtain lucrative subsidies’.

Her letter was described in court as one of six ‘protected disclosures’ she made to senior colleagues over the ensuing months. It contained claims that the company had acted grossly negligently in those representations given that ‘the people working for Drax… knew that Drax did not have the evidence it would need to confirm that it never sourced primary… logs for wood pellets’.

The day Ahmar sent the note, things took another tricky turn, after the company’s spokesman Dr Alan Knight appeared in the Commons before the Environmental Audit Committee.

She told the tribunal that Knight ‘misled Parliament by insisting that the biomass used was sustainable and by dismissing any concerns that biomass could also be coming from unsustainable sources. He knew we did not have the data to support those representations.’

Again, it should be stressed that Drax denies many of the claims Ahmar aired in court. And whatever had really occurred, it doesn’t seem to have taken her ‘protected disclosures’ at face value either. On paper, senior executives at a publicly-listed company, alerted to potentially serious shortcomings in their firm’s business practices and submissions to government, might be expected to thank the whistleblower who decided to bring the whole thing to their attention.

Yet at Drax, the exact opposite allegedly happened. In return for blowing the whistle, Ahmar claimed that she was forced out of a job, telling the court she was issued with an ultimatum: ‘Sign an NDA, take money and go quietly.’

Specifically, she stated that on January 10, 2023, she was offered ‘a sum of money [£50,000] to leave my employment and drop the protected disclosures.’

She said she was ‘told the offer was confidential and threatened that if I refused the deal I would be dismissed’.

Drax’s version of events is, again, different. In court, the firm instead argued that she was ‘unmanageable’ and, during her period of employment there, created a ‘maelstrom of chaos’.

It also said she had ‘lost the trust and confidence of multiple colleagues’ within weeks of taking up her position.

Drax claimed that Ahmar was an unreliable witness, and that her account of events had altered over time.

It said a KC who investigated her claims on behalf of the firm had concluded that: ‘[Ahmar] had generally adopted the attitude of “she is right and everyone else is wrong”.’

Out of fairness, it should further be observed that Ahmar is also no stranger to employment disputes. Early last year, she attempted to sue the Cabinet Office for ‘discrimination and harassment’ during her time there, which ended in 2022, only to withdraw the case.

She is also in dispute with energy company Essar which she briefly worked for in 2024.

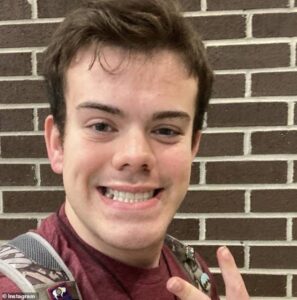

Further muddying the waters is the fact that she received help from a peculiar quarter in the shape of Louis Bacon, a bequiffed American hedge fund manager who helped finance her case. Bacon has previously sought to profit from Drax’s misfortune, having once taken a ‘short’ position against the power company, meaning that he would profit if its share price went down, although that position was closed in July 2024, before he began supporting Ahmar’s case.

Be that as it may, the early days of last month’s tribunal case were at times excruciatingly embarrassing for Drax, which not only saw Ahmar air damaging claims in open court but at one point watch as a senior executive named Jonathan Oates, who was her line manager, was brutally cross-examined about their interactions.

Oates was forced to concede that documents he had described as ‘contemporaneous notes’ of conversations with the whistleblower were in fact nothing of the sort, having instead been typed up from other records at a later date.

Last Monday was expected to represent a moment of even greater peril when chief executive Gardiner was to appear on the stand. But then came some remarkable news: the two sides in the employment dispute had suddenly negotiated a settlement.

The development meant that the case ended instantly. To the dismay of environmental campaigners, no further evidence was therefore made public.

Moreover, the settlement stopped Ahmar from commenting further on the detail of the affair, aside from via a joint statement which announced that both sides in the dispute had ‘reached a mutually agreeable position, without admission of liability’.

That statement continued: ‘Ms Ahmar made protected disclosures. Those disclosures were the subject of independent investigations instigated by Drax, as were other matters that Ms Ahmar raised about her employment.

‘The independent investigation into the disclosures has been shared with the regulator who reached a determination that is already public.’

The ‘independent investigation’ was, as it happens, an Ofgem probe. It ended in August with Drax paying £25million for what were described as ‘inadvertent and technical’ breaches of rules about disclosing where its wood came from.

Though this has been widely described as one of the biggest fines in British corporate history, the company insists, a touch comically, that the payment should be described instead as a ‘voluntary contribution to a redress fund’.

As for the cost of settling with the whistleblower, it remains unknown. However there were at least ten lawyers in court for proceedings and one observer estimates overall costs to be in excess of £6million.

In the parallel universe of ‘green’ energy subsidies that’s small change. In fact, it’s the exact amount British taxpayers pay every three days to a certain Yorkshire power station where two things seem to regularly go up in smoke: wood chips and the truth.