By QUENTIN LETTS FOR THE DAILY MAIL

Published: | Updated:

One hesitates to knee a man when he is down but Sir Justin Welby’s farewell television interview last weekend was depressing. It was not so much the content – an understandable desire to explain a few things after his resignation – as the personality of Sir Justin himself. There is no kind way of saying this: he was unexceptionable.

Few can doubt that Sir Justin, 69, tried his best as the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury, a line that stretches back to St Augustine; but viewers beholding this slight, managerial figure will have been underwhelmed. The merchant-banker-style spectacles. The open-necked shirt. The cardboard phrases evincing a grey, corporate character. Where was the grandeur of language? Where was the authority that should surely accrue after eight years as spiritual leader of 86 million Anglicans worldwide? Sir Justin will no doubt have been through personal turmoil since being toppled by accusations of Church child-abuse going ignored. But when he said he now hoped for ‘total obscurity – I would love never to be on telly again, in other words to disappear’, it was hard to resist thinking, ‘well that shouldn’t be too difficult to arrange’.

This is not just a Welby thing. The same applies to many like Sir Justin in our governing class. There are hundreds, even thousands of them. Dutiful but dull, they go through the motions of modern leadership, uttering the same bromides about due process and governance procedures. It is as if they have been programmed by human resources, individuality erased by formulaic managerialism.

Commerce and banking are not immune from this vanilla drift, as was apparent when Paula Vennels was put in charge of the Post Office. Her chief quality? She was said to exude an air of ‘Radio 4 respectability’. You find her ilk throughout Whitehall, in the regulatory agencies, charities and academia, even in our greatest universities. They burble away, leaving no more impression than the slenderest moth on a pillow. Across the entire seascape of politics: insipidness.

As the Mail’s parliamentary sketch-writer I watch these paladins of public life as they come before Westminster select committees. The governor of the Bank of England, Sir Andrew Bailey, fiddles with his chin and ums and ers. The world’s biggest tech companies send PR directors who might as well be area managers for Wiggins Teape. Trade union leaders sound like chartered accountants.

Whitehall mandarins are among the most forgettable. The only one with much evident panache is Dame Antonia Romeo at the Department of Justice. The rest? Third XI material at best. Take Sir Philip Barton, who just stepped down as permanent secretary at the Foreign Office. What a fantastic position that is. Sir Philip must have seen more life cross his desk in one week than most of us do in a lifetime. Previously he was our high commissioner to India and to Pakistan, two vigorous, vibrant countries. You thought: gosh, if he was posted there he must have something to him. But in the flesh there was seldom so pedestrian a specimen.

The Home office’s former permanent secretary, Sir Matthew Rycroft, was previously head of the Department for International Aid, ambassador to the United Nations and ambassador to Bosnia and Herzegovina. What an Alpha operator he must have been to rise to such magnificences, an innocent onlooker might think. Yet Sir Matthew was a stuttery hand-wringer. Simon Ridley, his deputy, looked so nervous that an airline steward would have handed him a sickbag. These two made Justin Welby look suave.

The quangos are no better. MPs summoned Lady Manzoor, who chairs the Financial Ombudsman Service. She was under pressure about the departure of her chief executive. Lady Manzoor curled into the defensive ball of a put-upon woodlouse. She was ‘no-comment’ made flesh. It was pitiful.

We could be ruled by dazzlers who gallop for the horizon and make us follow them from sheer force of charisma. Instead, our governing class shrivels. Why? Does human nature not tend to laughter and difference? Such things, however, will hold you back in modern civic life. Play it safe. Say nothing interesting. That’s how to ascend the greasy pole. Tall poppies are scythed. Flair is regarded with suspicion.

This has led to some commentators talking of Britain being in a ‘normie doom spiral’ – a disappearing eddy of ‘normies’, or dullards. A Parade of Plodders. The smack of command has been replaced by something limp and timid. Modern managers think this approach is friendlier. Actually it is less democratic, for promotions are made according to orthodoxy rather than individual merit.

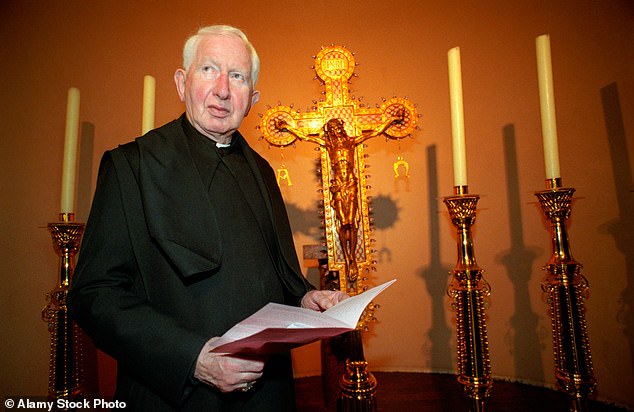

Half a century ago the British establishment was not short of fizzers. Michael Ramsay was Archbishop of Canterbury, wriggling his Old Testament eyebrows at the world. The BBC was chaired by Sir Michael Swann, a molecular cell biologist and war hero. The cabinet secretary was razor-sharp Sir John Hunt, punctiliously impartial and, as it happened, brother-in-law of the Benedictine monk Basil Hume. Hume became Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster and was the most ‘papabile’ Englishman (ie best qualified to be a pope) for some 400 years. Today we have four British cardinals. Can you name more than one of them?

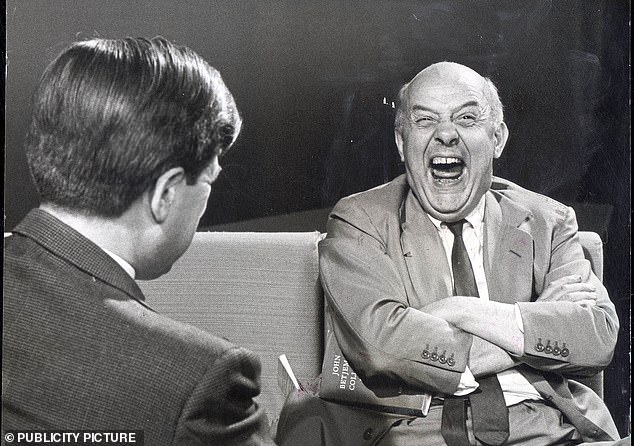

The Poet Laureate of the mid-1970s was Miss Joan Hunter-Dunn’s suitor, Sir John Betjeman. The Booker Prize’s shortlist included C.P. Snow, Kingsley Amis and Beryl Bainbridge. Across the legal world strode two salty jurists: the Master of the Rolls, Lord Denning, and that harrumphing contrarian Quintin Hogg as Lord Chancellor. Denis Healey, once a beachmaster at the Battle of Anzio, was Chancellor of the Exchequer. He, too, had bushy eyebrows. The Master of Balliol was the Marxist historian Christopher Hill. On television Michael Parkinson’s chat-show guests included Peter Sellers and Muhammad Ali. Ideas flew as fast as fists.

Politically and socially these people were a mixed bag and they were interesting. Would they have prospered in 21st century Britain? Sir John Betjeman was not safe in taxis. Sir Kingsley Amis was difficult after lunch. Dame Beryl Bainbridge smoked like a Drax power station. With today’s political filtration systems they would soon have been cancelled for being insufficiently worshipful towards, say, Black Lives Matter or Just Stop Oil. Breakfast television would have sent them to Outer Siberia. Whitehall’s honours committee would have given them a swerve.

Our country’s glittering prizes now go to duds, from the prime minister down. Sir Keir Starmer proudly says he is not bookish and that he does not dream. This is depressingly believable. His speeches are as thin as skimmed milk. Kemi Badenoch and Sir Ed Davey have as much hinterland as mud-flats. Beyond Angela Rayner and Nigel Farage, few politicians break out of the straitjacket. Even Mr Farage is now in danger of being gelded by his party’s new chairman.

You may accuse me of nostalgia, of a sepia-tinged belief that everything was better in the old days. No they weren’t. The past was repressed. Logically it should therefore have been more boring. Class rigidities have eased, thank heavens, so why are our leaders not more colourful? Why has the governing elite never felt more like a different, disapproving caste?

One person involved in the vetting of top public appointments suggests that ‘the Establishment has, since Brexit, lost its nerve’. Another, who served in Boris Johnson’s cabinet, adds: ‘Public life has been rotten for decades. Since the 1970s, with the exception of the Thatcher years, the Establishment’s objective has been managed decline.’ Bogus egalitarianism is also to blame. Public bodies are told to promote minority representation. Big jobs go to middlers.

The Master of Balliol today, far from being a scintillating Leftwing thinker, is a right-on former pen-pusher, Dame Helen Ghosh. Previously she turned the National Trust from national treasure into a woke horror-show. Emmanuel College, Cambridge, once had that witty peacock Norman St John-Stevas as its Master. His successor today is Sally Morgan, scowling ex bag-carrier for Tony Blair. The master’s lodge at Trinity, Cambridge, grandest of all colleges, is occupied by Dame Sally Davies, the former chief medical officer who was forever telling us what not to eat and drink. Maybe she should have spent more time worrying about pandemics.

As recently as the 1990s Sir Chris Woodhead was the head of Ofsted. Sir Chris was an eloquent, bold campaigner for education. The only person who approaches him today is the London headmistress Katharine Birbalsingh, yet she is ostracised by the establishment.

The new cabinet secretary, Sir Chris Wormald, attended a Commons select committee last month. He came across as little more than a backroom wonk. Sir Chris replaced Simon Case, who was too young and impressionable for the job. In earlier decades both men would been lucky to run on with the half-time oranges.

How about the Royal Society, our national academy of the sciences? I looked at the first 10 pages of its website’s list of fellows and recognised only one of them (Kate Bingham, who led the Covid vaccines taskforce). The rest may well be fine researchers but they are not prominent in national life.

Is it not important for our society to celebrate and to be exposed to its greatest minds? It is the same at the British Council and the Royal Society of Literature. Roger Lewis, an author of rare spark, has repeatedly had his hopes of becoming a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature rebuffed. Roger, you see, can be a little argumentative. But what is so terrible about that? Writers are meant to be bolshy.

Public intellectuals were once encouraged to say what they thought. John Freeman conducted ‘Face to Face’ interviews with prominent thinkers of the 1960s. They included the controversial MP Bob Boothby, the writer Dame Edith Sitwell, Sir John Reith, Evelyn Waugh and Compton Mackenzie. They raised their chins and spat out their opinions. In the early 1990s the programme was revived and even then the list had some interesting people: Anthony Burgess, David Hare, Vanessa Redgrave, Germaine Greer. If ‘Face to Face’ were revived today, imagine the anguish about ‘giving a platform’ to people whose opinions might upset the fainthearts. We have allowed prudes to suffocate ideas.

The Royal National Theatre is chaired by a low-profile businessman, Sir Damon Buffini. How often do we hear sparky contributions to national debate from him or the theatre’s director, Indhu Rubasingham? She’s hardly another Peter Hall, is she? The president of Riba, the architects’ body, is Muyiwa Oki. At 32 he is too inexperienced to bring much to the feast. The National Gallery’s director, Mary McMahon, seems more interested in political correctness than in art’s emotional depths. The Arts Council is in the grip of that cold fish Sir Nicholas Serota, the box-tickers’ box-ticker. Even the Chelsea Flower Show has gone trendy and dull. Its president? A chap called Keith Weed. Says it all, really.

And so we slide into drabness. Young entrepreneurs are denied business role-models such as Sir John King and Anita Roddick. The supreme court being filled with characters from the Observer Book of Brians, our notion of justice is anaesthetised. Even pop music has become unadventurous. The energy of punk has ebbed to something altogether more tame. Pulses slow, appetites wane, the nation slowly subsides into lassitude. And our ‘normie’ elite thinks ‘job done – we’ll be safe in our jobs now’.