Turning animal poo into offspring sounds like a zoo keeper’s conjuring trick, but it might become a reality if researchers succeed in a new project to help save endangered animals from extinction.

From snow leopards to sea turtles, animals the world over are under threat, with some scientists calling the massive loss of wildlife in recent decades a “biological annihilation”.

Now researchers are exploring whether they can use dung to capture – and harness – animals’ genetic diversity.

Hailed “the poo zoo”, the project is based on a simple premise: besides being rich in undigested food, bacteria and bile, poo also contains cells from the creature that deposited it, shed from the lining of their intestines.

Crucially, research has suggested some of these cells within the poo are still alive – at least when the deposit is fresh.

“It’s very, very early stages,” said Prof Suzannah Williams of Oxford University, who is leading the team. “But so far it’s feeling very positive,” she added, noting they have not only isolated live cells from mouse poo, but also from elephant dung.

The hope is these cells could be used to help boost genetic diversity within populations, thereby increasing the chance of species surviving.

The approach, known as “genetic rescue”, can take several forms. In the first place, DNA from the cells could be analysed to help scientists understand the genetic variation of different populations, informing various conservation efforts. That DNA is of higher quality if extracted from cells that are alive.

But if cells from poo can be cultured and grown it raises another possibility: the creation of entire animals using state-of-art assisted reproductive technologies.

These include cloning – in which the nucleus of a cell is inserted into a donor egg, an electric impulse is applied, and the resulting embryo is implanted into a surrogate to produce a genetic “twin” of the original animal.

Perhaps more exciting still is the possibility of reprogramming the cells so that they have the capacity to become any cell type. Crucially, research in mice has suggested such cells can be turned into sperm and eggs – meaning they could be used in IVF-type techniques to produce offspring.

“If you use eggs and sperm, you get to leverage sexual reproduction and all of the recombination that happens during those events, and you get to really start to build the potential for adaptation to environmental stress,” said Dr Ashlee Hutchinson, who came up with the idea of the poo zoo and is a programme manager of Revive & Restore, a US-based conservation organisation that is funding the work.

Put simply, by creating sex cells in a laboratory, it is possible to harness the genetic diversity of a species without having to bring together individual animals – who might be in different parts of the world, or otherwise inaccessible – or needing to collect their sperm and eggs.

Reprogrammed cells could also allow scientists to use gene-editing techniques to understand, for example, the genes involved in wildlife diseases or environmental adaptations – information that could subsequently be used to engineer greater resilience into a species, for example by screening sex cells or embryos for certain genes, or even through gene editing.

Gene editing is already being explored by Revive and Restore to bring back the extinct Passenger Pigeon, and by the bioscience company Colossal in an attempt to revive the woolly mammoth.

Freezing cultured cells in liquid nitrogen at -196C means they can be preserved indefinitely, allowing the DNA they contain to potentially be used in applications not yet dreamed of.

The biobanking of cells and tissues of endangered species, from semen and ovarian tissue to skin cells, for genetic rescue has already been embraced by charities and organisations, from the UK-based Nature’s Safe to San Diego’s Frozen Zoo.

But this typically involves taking cells or tissues from the animal itself, whether alive or after it has died. By contrast, taking cells from poo is non-invasive and does not involve capture, raising the possibility of collecting them from even the most elusive creatures – an approach that could enable scientists access to greater genetic diversity by sampling wild populations.

“It’s a case of how can we, en masse, collect living cells in as many species as we can to maintain diversity that we’re losing at a terrifying rate,” said Dr Rhiannon Bolton, a researcher on the project from Chester zoo, a charity that is collaborating on the project.

But the approach is not without challenges. The sheer volume of dung that must be processed is considerable – “think about buckets and sieves at the beginning,” said Bolton.

after newsletter promotion

What’s more, poo contains more than just animal cells and organic waste.

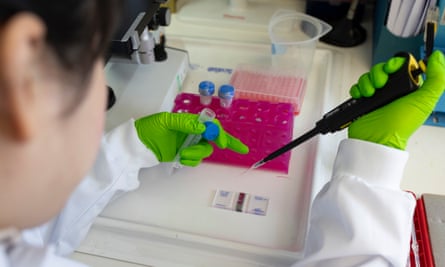

“This is the most bacteria-heavy environment you could possibly collect cells out of,” said Williams. The team are already working on a solution – using dilution to remove the bacteria.

“Then we culture [the animal cells] in antibiotics and antifungals,” Williams said.

But even if living cells can be isolated from poo and cultured, there are hurdles to clear before offspring can be produced. Among them is the lack of understanding of the reproductive physiology of many animals, meaning the focus, at least initially, is likely to be on well-studied species.

Yet while the poo zoo is in its infancy, the team have form: Williams also leads an endeavour to save the northern white rhino by using lab-based methods to produce a large number of eggs from rhino ovarian tissue while, among other projects, Revive and Restore has been involved in the successful cloning of the black-footed ferret – a species twice thought to have gone extinct – from cells frozen decades before.

Some conservationists, however, maintain prevention is better than cure.

“The best way to protect species is to stop them declining to the point that such approaches as cloning are required. While these new technologies might provide some exciting opportunities for conservation they are unlikely to provide the transformation we need to see,” said Paul De Ornellas, the chief adviser on wildlife science at WWF UK.

“Addressing the primary drivers of biodiversity decline like habitat loss and overexploitation while supporting conservation efforts at scale that enable the protection and recovery of nature must be our primary focus if we’re to address the biodiversity crisis.”

Dr David Jachowski, an associate professor of wildlife ecology at Clemson University and an expert on the black-footed ferret, added that while persevering genetic diversity is important, it is not enough on its own.

“Producing more animals doesn’t necessarily mean you’ve removed the threat in the wild to release the animal and have it survive,” he said.

But the poo zoo team say modern and traditional methods can work in parallel.

“I’m not saying we should stop protecting habitats and stop doing in situ conservation efforts,” said Bolton. “I just think because of the dire straits we are in, you need to try multiple different tools”.