Dawn broke on a foggy morning on Terminal Island, an artificial slice of land that rests where the city of Los Angeles meets the Pacific Ocean. Sea lions barked in the distance as sleek, white SUVs drove through a checkpoint into a federal prison. Chavo Romero, his hair pulled back in a ponytail, sipped coffee as he watched them.

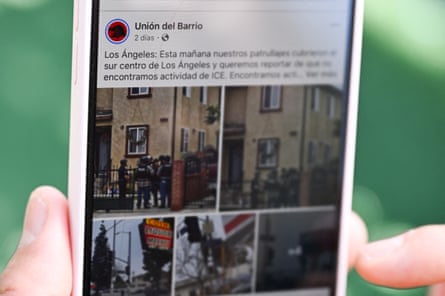

He awoke before daybreak, taking the day off from his public health job to drive here in the dark. Romero is part of a coalition of trained volunteers called Union del Barrio, who patrol the barrios, or neighbourhoods, to look for immigration enforcement, “La Migra.” When they spot Ice activity, they post videos that go viral, alerting people to seek shelter.

Since June, Union del Barrio volunteers have been patrolling Terminal Island, where they say federal immigration agents have been staging enforcement operations. Agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice), Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and other agencies arrive here early in the morning, Romero said, before being dispatched to conduct raids across southern California. “They’re clocking in to go kidnap people. They see us, they flip us off.”

By arriving early at Terminal Island, the volunteers have a strong vantage point to alert their larger network about which vehicles are leaving the staging area – sending photos that show the make, model, color and plate number. This enables immigrant communities to be on the look out for these vehicles. For instance, Romero said they have seen the same large white van on Terminal Island that was also involved in a violent raid at a cannabis farm in Ventura county. More than 200 people were arrested and one man died.

The patrol’s work is personal for Romero, who is from the farming community of Oxnard in Ventura county. His parents are fieldworkers who are Indigenous to Mexico – his dad is Tepehuan and his mom is Guachichil. Romero, who wore an army green Union del Barrio t-shirt on this July morning, joined the group 30 years ago.

The Los Angeles patrols date back to 1992, after the riots that erupted when officers were acquitted of brutally beating Rodney King, and in recent months they have emerged as a beacon of resistance as California becomes a frontline for raids against immigrant communities. The mass arrests reached a violent crescendo in June, when agents in military-style clothing grabbed people with brown skin off the streets of Los Angeles, dragging them into vans and locking them in detention facilities.

On 11 July, a judge issued a temporary restraining order restricting agents from arresting people based on race or occupation anywhere in the Central District of California, a federal court that serves over 19 million people in southern and central California. The order slowed arrests in Los Angeles, but didn’t stop them. And immigration enforcement received a windfall this month of $75bn from Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, noted Romero.

“We’re tripling down on our patrols,” he said. “The whole order was to end racial profiling … But the restraining order doesn’t say stop the deportation and detention.”

“That will never stop,” he added. “It’s a multi-billion dollar industry that needs to keep going.”

‘The city is under siege’

Life for immigrants in the US has become more precarious since Donald Trump took office and declared an emergency at the US-Mexico border, paving the way for raids in the 100-mile border zone, including Los Angeles. But few were prepared for just how dire things have become.

In June, federal agents wearing mirrored glasses and ski masks swept through Home Depots, car washes and street vendor stands. They approached people with brown skin in the barrios, demanding to see IDs and asking where they’re from. They tackled people and dragged them into unmarked vans. According to a lawsuit filed by the ACLU, agents typically had no warrants or prior information about the people they arrested – they approached them based on skin color or occupation.

Keli Reynolds, a Los Angeles immigration attorney and founding partner of Olmos & Reynolds, has worked immigration cases under five administrations stretching back to George W Bush. “I’ve never seen it like this, and I’ve been practicing for 20 years,” she said. “The city is under siege. People are terrified.” She noted that none of her clients who were detained since the siege began in June had criminal records.

“They were detaining people, tackling them, and there was absolutely no reasonable suspicion,” she said. “They were sweeping areas and detaining, I would say, almost 100% Latinos, anybody with brown skin.”

In her 11 July order, the judge agreed with the ACLU that there was “a mountain of evidence” to support the allegations. But she acknowledged that the federal government is allowed to carry out large-scale immigration enforcement in Los Angeles. The order essentially tells Ice to follow the constitution, Reynolds said.

The White House denies that agents have targeted people based on skin color. On 18 July, in response to a reporter’s question, Kristi Noem, the Homeland Security secretary called it a “false narrative that has been put out there in the media”. She scolded the reporter: “Don’t you dare ever say that again.”

Ice agents appear to have shifted their strategy since the order, Reynolds said. They are now picking people up outside their homes while claiming to have warrants, whether or not they actually produce one.

Renyolds said in one case in LA County, her client was detained by agents who did not identify themselves. “They told her they had a warrant but they didn’t show her a warrant. And she even asked to see a warrant, and they said they didn’t have to show it to her,” she said.

In another incident reported by LA Taco, agents tried to arrest a woman at her Huntington Park home, but the community confronted them and demanded a warrant.

Federal agents continue to target Home Depots, but now it’s happening outside of the Central District, Romero said. On 22 July, Union del Barrio posted a video showing Ice agents detaining two workers at a Home Depot in Encinitas, outside of the zone protected by the order.

‘We’re not backing down’

Los Angeles has not returned to normal. The barrios remain cautiously quiet. Street vendors have returned to the sidewalks, although in smaller numbers. People check social media for Ice activity before running errands.

“We’re treating it like a cease fire,” said Ron Gochez, founder of Union del Barrio’s Los Angeles chapter. “During a cease fire, you have to regroup your forces, because you know it’s going to start again.”

The group’s patrols are a model for the larger Community Self-Defense Coalition, which holds training sessions to teach people to document Ice activity. Union del Barrio is using this time to train more volunteers. Gochez estimated they have trained 750 people since the court order.

Gochez is skeptical that the Trump administration, which has routinely defied the courts, will continue respecting the order. “We don’t anticipate the Trump administration respecting this if it doesn’t go his way,” Gochez said. “What we anticipate is three and a half more years of repression against us.”

The raids are part of a 500-year anti-colonial struggle, Gochez said. “We know we’re going to take losses, but in the end, we’re going to win.”

Back on Terminal Island at around 7.30am, a black four-by-four truck with a federal plate pulled up and a man stepped out, watching the volunteers. Romero believed they were being surveilled.

In June, Union del Barrio found itself in the crosshairs of the administration. Josh Hawley, a Trump ally and chair of the Senate subcommittee on crime and counterterrorism, sent a letter accusing them of “aiding and abetting criminal conduct” and providing “logistical and financial resources” in relation to the resistance protests. Union del Barrio rejected the allegations, noting that protesters were responding to “a rapidly growing number of intentionally cruel, increasingly violent, militarized immigration operations across the United States”.

“They were asking us to voluntarily cease and desist,” said Romero. “We were like: ‘We’re going to voluntarily tell you no.’”

As he spoke, Romero was interrupted by the thrumming of an LAPD helicopter overhead – a familiar sound in the Los Angeles barrios. It flew over the group several times.

Romero views the city as a frontline. “Los Angeles is the most heavily populated urban center of Mexicans north of the border,” he said. “If they’re able to crush the LA resistance, that means they’re going to be able to do it anywhere else. That’s why LA as a frontline has been a critical space to show that the community is organized, and we’re not backing down.”

He feels proud of the city for providing an example of how communities across the country can resist raids. “They really thought they were going to come in and scare everyone into their corners, but this is LA — and LA is resisting.”