Russian words echo through the corridors of Gonjiam middle school as a woman from Uzbekistan addresses a classroom of teenagers still grappling with the Korean language.

“How do you speak with Korean friends?” she asks. The responses are halting. Some use translation apps. Others rely on classmates who speak better Korean to navigate school life.

They are ethnic Korean children, mainly from former Soviet republics, caught between cultures in a country to which their parents moved for work and stability.

Their instructor, Luiza Sakhabutdinova, an assistant professor who came to South Korea 17 years ago, is one of 39 mentors from 21 countries deployed in programmes nationwide to foster social cohesion.

The sessions, part of a government-led programme in the city of Gwangju near Seoul, offer a glimpse into the country’s approach to multiculturalism, where integration is not unfolding organically but is being carefully managed.

Aleksei Niu, a 17-year-old from Russia placed two years below his grade level, is still struggling with the Korean language but appreciates the support he receives. “I wish there were more lessons like this.”

Hwang Byung-tae, the school’s head teacher, points to success stories, including a former foreign student turned teacher at the school, as well as those who progressed all the way to university. “Many foreign students who come here adapt well and succeed,” he says proudly.

A demographic milestone

South Korea has traditionally been cautious toward immigration, priding itself on ethnic homogeneity. However, the country is edging toward a demographic milestone.

With 2.11 million foreign residents as of June, accounting for 4.1% of the population, South Korea is nearing the 5% threshold that experts use to define a multicultural society.

Economic reality is driving this shift. South Korea’s fertility rate has fallen to 0.75, the lowest in the world, and its working-age population is projected to halve by 2070. Young Koreans, meanwhile, increasingly avoid jobs in manufacturing, agriculture, and construction – sectors now kept afloat by migrant labour.

South Korea is trying to actively shape these changes in its demographic makeup. Its approach, using services and outreach, promotes the country’s desire for cohesion, predictability and cultural unity.

“We want migrant children to have equal opportunities in Korean society,” says Park Chang-hyun from the justice ministry’s immigration integration division. “We want them to adapt well into society and be culturally comfortable so they can showcase their capabilities and talents.”

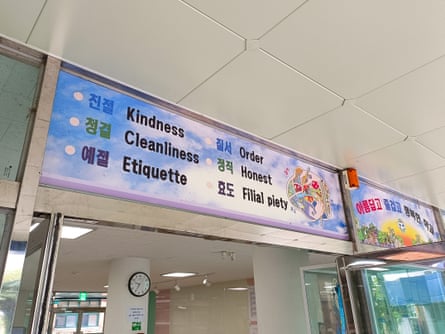

In schools like Gonjiam’s, this approach is evident in language support, after-school mentoring, and localised intervention. Nationwide, the government designates certain areas as “multicultural zones” and integration programmes target specific groups, primarily ethnic Koreans from abroad, women from south-east Asia who marry Korean men and labourers in designated sectors.

Immigrants as ‘labour units’

Nowhere is this approach clearer than in Ansan, an industrial city 25km southwest of Seoul that has become the government’s de facto multicultural laboratory.

Home to the Banwol and Sihwa industrial complexes, Ansan has long attracted migrant workers, similar to other cities like Gwangju, albeit on a far larger scale. Today, 14% of the city’s population are foreign nationals from 117 countries, the highest proportion in the country. In the Wongok-dong neighbourhood, the figure rises to 84%.

At Hope365, a nonprofit support centre, early adaptation courses run in 18 languages, covering everything from opening bank accounts and navigating healthcare to understanding Korean values and basic laws. Volunteers cook for immigrant children and provide after-school tutoring.

Kim Myeong-soon, a Chinese Korean mother, has enrolled her child at the Hope365 centre. “My kid really loves it and is getting a lot of help,” she says. “The children here come from diverse backgrounds – Persian, Korean, Chinese, and despite some language barriers, they share different cultures and get along well together.”

Just down the road, the foreign resident support centre offers Korean language classes, community services, and a multilingual library, part of the city’s substantial investment in immigration infrastructure.

Yet even here, where multiculturalism seems most advanced, well-intentioned efforts confront deeper structural challenges.

The “employment permit system”, which governs most foreign labourers, gives employers outsized power over their staff, making it difficult for workers to escape exploitation or switch jobs.

Critics argue that South Korea’s approach still treats foreign workers primarily as labour units rather than as people seeking to build lives in the country, with many workers often enduring mistreatment including physical violence, and poor working conditions.

A lithium battery plant fire in 2024 killed 23 workers, mostly Chinese nationals, underscoring the disproportionate risks foreign workers face, activists say.

More recently, a video showing a foreign worker tied to bricks and lifted by a forklift at a factory prompted president Lee Jae Myung to condemn what he called a “blatant violation of human rights.”

In Ansan, the same support centre that hosts integration classes also doubles as a complaint office, handling a steady stream of cases involving wage theft, threats from employers, and workplace abuses.

‘One-sided’ education

A 2024 survey by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) found that over 61% of Koreans now consider having foreign residents in their neighbourhood normal.

Yet acceptance varies sharply by context and migrant type. While 79.7% support child allowances for permanent residents, only 45.3% back such benefits for migrant workers. Koreans also show higher acceptance in public spheres like workplaces than in private relationships.

Concerns about public spending, crime, and job competition persist.

Many migrant residents still face discrimination in daily interactions and sectors like banking. They have little recourse, as the country has never enacted comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation.

A recent high-profile case in the south-eastern city of Daegu, where vehement opposition to the reconstruction of a small mosque included pigs’ heads left at the site, highlighted tensions.

According to KIHASA’s YoonKyung Kwak, current integration efforts are “fundamentally one-sided” as they focus on educating migrants, not the host society.

“What truly matters is whether Koreans see migrants as equal members of society – not merely as temporary workers or economic tools,” she said. “Moving beyond an instrumental perspective toward a genuine sense of shared community is the next critical step for meaningful integration.”