The rocky crevices of the Valdés peninsula and the pristine waters of the San Matías Gulf, on the Atlantic coast of Argentinian Patagonia, are a remote sanctuary for marine life, where protected southern right whales breed, orcas hunt and thousands of penguins and sea lions flourish.

“It’s a treasure chest of wildlife – a breathtaking, untouched place,” says María Leoní Gaffet, a local wildlife expert and co-director of Península Valdés Orca Research. “It’s unique in the world.”

But, she says, this rich ecosystem and Unesco world heritage site could soon be lost. A consortium of oil majors led by the state-run energy company YPF, along with Shell and Chevron, is pushing ahead with plans for the country’s largest crude oil export port and a fossil gas liquefaction ship in the gulf.

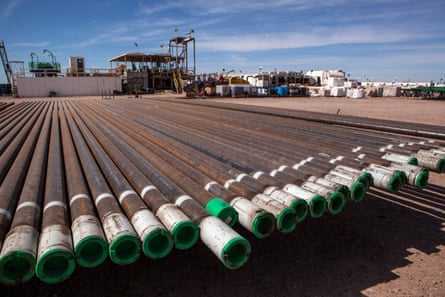

Part of the Vaca Muerta Sur project, the infrastructure involves constructing a 271-mile (437km) pipeline, which is due to enter service in late 2026, from the Neuquén basin to an export terminal at Punta Colorada on the Atlantic coast.

The pipeline is designed to transport 550,000 barrels per day (bpd), or 88,000 cubic metres, by 2027, with the possibility of increasing capacity to 700,000 bpd. There will be a storage facility able to hold 4m barrels and a large-capacity tanker will dock every five days.

“The oil companies are moving in, and nobody is talking about it,” Gaffet says. “The situation is desperate.”

Since taking office in 2023, President Javier Milei – a climate-crisis denier – has dismantled Argentina’s environmental protection policies, abolished the environment ministry, cut funding and threatened to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement.

But those who object to the project warn of the potential for catastrophic consequences for local fauna, including the world’s largest colony of Magellanic penguins. San Matías Gulf borders the Península Valdés protected area and nearby reserves, including Islote Lobos national park and Caleta de los Loros.

“It will have a disastrous impact on biodiversity, from the smallest marine life up to the whales and orcas,” says Gaffet.

The primary concern is the threat of oil spills. María Raquel Perrier, a marine biologist, says oil ports are “inherently dirty” and even the “inevitable microspills” can deprive water of oxygen.

“These spills kill vulnerable species and disrupt the entire biodiversity system,” says Perrier.

For example, oil strips the insulating qualities from the fur of sea otters, making them prone to hypothermia, and clogs up the feathers of birds, stopping them from flying.

The gulf’s semi-enclosed geography also means polluted water lingers, says Perrier, who warns that Argentina is ill-equipped to respond to potential spills. “In one case earlier this year, we only found out [about a spill] because fishers said the sea had turned black,” she says.

Diana Visintini, who runs whale-watching tours, says increased maritime traffic also raises the risk of collisions. “We already see, from the scars on their backs, where propellers have hit whales in the outer seas. Imagine what could happen if oil traffic comes here,” she says.

Once hunted to near extinction, southern right whales now number about 5,500 in the area. Visintini says studies in Massachusetts, in the US, show that oil tanker collisions are a major cause of the population decline of a similar species, the North Atlantic right whale.

The Buenos Aires-based Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas has warned that industrial noise pollution in the gulf could further harm whales, hindering communication, creating chronic stress and disrupting migration patterns.

Coastal communities dependent on fishing and tourism also feel threatened. Sergio Fernández, a 60-year-old fisher and guide, says: “All the people living and working here, we are all at risk. Any spill will be huge; it will be a storm. The only people it won’t affect are those who invest.”

Oil spills contaminate water, air and food with toxic chemicals such as polyphenols and benzene, and can cause serious health problems. Cecilia Salcedo, a 44-year-old teacher, fears for her children, foreseeing “a sea they can’t swim in; a sea that’s privatised, taken over by corporations”.

Opponents of the project say they have been excluded from any debate. Fabricio Di Giacomo, 43, a resident who is a member of the San Matías Gulf collective, says only two public hearings have been held about the project. He adds that those opposed to the project have faced intimidation from locals who support it. He has footage of a hearing in the Río Negro town of Sierra Grande in 2023 when campaigners were blocked from entering.

“There were 10 or 15 men waiting for us outside,” he says. “They said we couldn’t be there and blocked the entrance so that we couldn’t get in.

“I was officially registered to speak at the assembly. But these men were threatening me, saying they would kill me.”

Gaffet and Visintini argue that the oil terminal should be moved to open waters. “We’re not saying they shouldn’t extract the oil,” Gaffet says, “just take it to the open sea at Viedma, or through Buenos Aires province, which already has a port.”

“Why should we sacrifice another area? Because they want to build the cheapest pipeline possible? The price is too high, to lose this nature so a few people get rich.”

Shell did not respond to requests for comment. Chevron said YPF should comment on the case, as the Argentinian company was the leader of the consortium.

YPF responded in a statement on behalf of the consortium, saying that the project would create thousands of jobs.

“At its peak, it will create over 5,000 direct jobs, as well as thousands of indirect jobs across related sectors.”

The statement did not directly comment on the dangers of oil spills, but said an environmental impact study was approved by Río Negro’s energy secretariat in 2024 and was subjected to a public hearing.

YPF said: “The study, carried out by two internationally recognised consultancies, involved various field surveys with the participation of up to 50 specialists, including terrestrial and marine biologists, fisheries engineers, oceanographers, sociologists, architects and others.”

The Río Negro and Chubut provincial governments did not respond to requests for comment. But the Río Negro administration has previously said the project’s impact would be “moderate to low”.

Meanwhile, Visintini and the local fishers have begun oil spill response training. “We have to be prepared for what might happen,” Visintini says.